This article is part of a series looking back on previous vintage reports. All reports were originally published 2 years after the vintage. The 2018 vintage report was published in January 2020, the 2017 vintage report was published in January 2019, etc.

Overview

A cold coming they had of it: 2016 in the Côte d’Or and Chablis was both challenged and defined by the harsh April frost. It killed the nascent buds in many vineyards, it delayed ripening and sharply reduced yields. As a result, the wines from frost-bitten vineyards are more concentrated than from those that were spared.

Further extreme weather affected all growers: severe mildew attacks, sunburn and drought contributed to a vintage that is difficult to compare with any other, and in which growers had to work unusually hard to produce good wine.

But produce it they did. 2016 is a lovely vintage in a classic style, with dense, ripe yet crunchy fruit, plenty of energy, and excellent terroir definition beneath.

Growing Season

The winter in 2016 was warm and damp, and never dropped below freezing, except in Chablis, and there was a severe and widespread hailstorm in early April in the Maconnais. Budbreak was promising, and heralded a generous crop. But then for two successive nights, the temperatures dropped to just below freezing, causing significant damage – the worst since 1981 – and many vineyards that had escaped the first round were clobbered on the second.

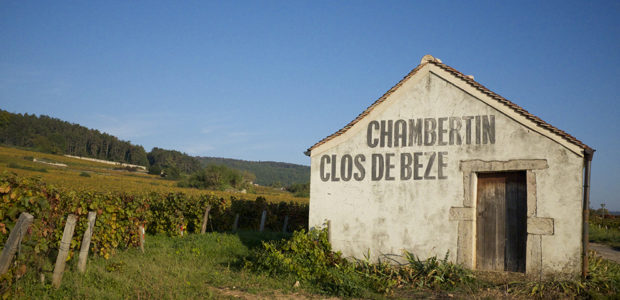

Astonishingly, vineyards never previously affected by frost were hard hit – Montrachet, Musigny and Chambertin, for instance; in Chablis the effects were severe, but they are used to it there, and counter-measures provided some relief. So why was the damage so bad in sites where frost had never struck before? There are many theories, and no easy answer. It seems two types of frost were involved. The first was due to cold air flowing down the hill and along valleys, the most common type of frost in Burgundy. The second was due to a series of unfortunate events: rain on 26th had left the ground humid, but that night the sky cleared, and the following morning, the ice that had formed on the nascent leaves and buds acted like a magnifying glass for the rising sun, burning them black.

There were many local variations depending on exposure, wind, and elevation; guyot trained vines (primarily white vines) suffered more than those using the cordon de royat system, as the latter were slower to develop and had fewer leaves and buds; walls provided some protection, as did trees, and cloud cover – most famously over Puligny for a brief thirty minutes – against the sun.

Cool, damp weather followed throughout May, with two nasty hailstorms in Chablis, and June was no better. There were severe attacks of mildew, to which frost weakened vines were particularly vulnerable, and which required nimble treatments. Many organic growers, with limited remedies at their disposal, suffered huge losses or resorted to conventional methods.

At the end of June the weather turned, remaining fine and dry until the harvest at the end of September. Many vines were affected by drought, and some grapes got sunburn. The harvest took place in perfect conditions.

Conclusion

You might wonder how weather like that can produce anything of substance. Many growers were not optimistic, but as the wines developed in cask they were very pleasantly surprised. The extremes of weather – cool and damp, then warm and dry, have given the wines definition on the one hand, and phenolic ripeness on the other. Frédéric Lafarge spoke of the joy of the survivors, and there is certainly an exuberance and energy in the wines to match the ripe fruit. The frost-bitten wines are concentrated, and some of them unrelaxed, especially the whites, but in the medium to long term they will provide lovely drinking.

Many growers have not increased prices, some have posted modest increases, but the fall in the value of the pound has not been helpful.